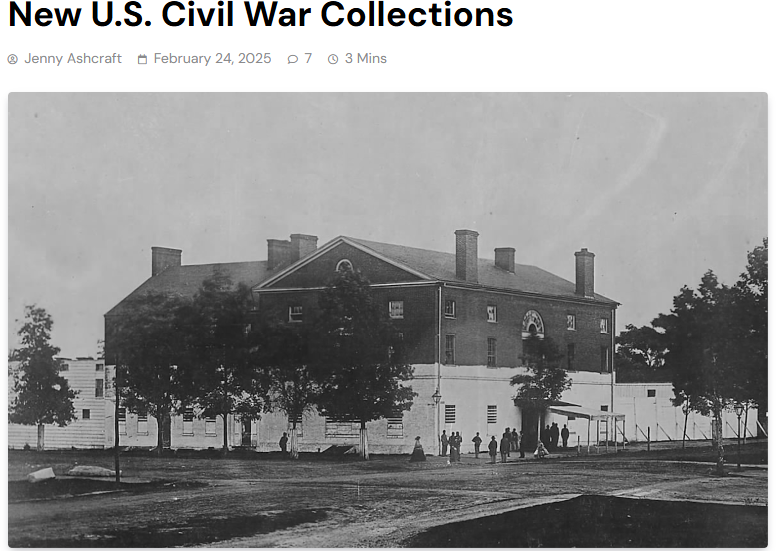

While I’m a fan of all of Ancestry’s offerings, I’ve found that Fold3 is easily one of my favorite subscription sites. As someone who’s passionate about studying the American Civil War and the brave soldiers who fought in the conflict, I appreciate Fold3’s millions of records that are related to the conflict. Because of this, you can probably imagine my excitement when I received an email that Fold3 has two new Civil War collections that were recently uploaded: the Civil War Prisoner of War Records, 1861-1865 and Civil War Lists of Persons Employed in Army Hospitals, 1860-1865.

So, what can researchers expect to find? Per Fold3, The Civil War Prisoner of War Records “contains some 1.6 million records for both Union and Confederate POWs. Each soldier’s name is indexed and searchable.” Meanwhile, Fold3 claims the “second new collection contains the names of female nurses, cooks, and laundresses employed at Army Hospitals during the Civil War.” Going further, they also state that this “single volume is not a complete list and does not include all hospitals or all women who served in these roles.”

While I was excited just reading about these new offerings, I was on Fold3 in a matter of a couple of hours post-announcement, ready to research my grandfather who was held at (and later died in) the notorious Andersonville prisoner of war camp. Read on to discover just what I learned in my search, plus some helpful tips!

What I Learned About My Grandfather

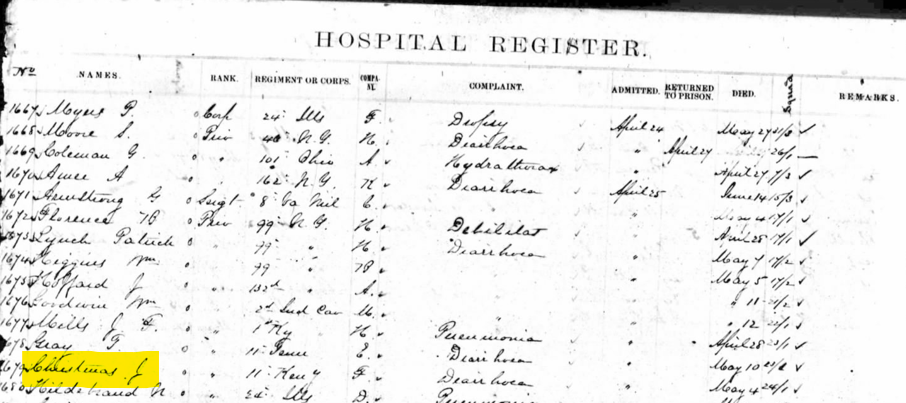

As I started researching my Civil War grandfather, Jesse Christmas (whose name is highlighted in the record above), I wasn’t exactly sure what to expect. Within a matter of a couple of minutes, though, I’d located the Hospital Register above that features my grandfather’s name, regiment, company, “complaint” (or disease), when he was admitted, his date of death, and his “squad” number.*

Although these pieces of information–like my grandfather’s regiment and death date–might seem quite ordinary, the record still offered up new-to-me details. For starters, while I knew my grandfather had passed away due to diarrhea (which unfortunately plagued many Andersonville prisoners and Civil War combatants in general), I never knew for sure if he had been admitted to the hospital.

While it might seem perfectly natural, even positive, for an ailing soldier to be carted off to the hospital for care, that was unfortunately not the case at Andersonville. In fact, conditions were so deplorable that many soldiers opted to die surrounded by their comrades, rather than in the callous, unsafe environment of a hastily-constructed medical facility. John Ransom, a Union captive at Andersonville, wrote the following about Andersonville’s so-called hospitals: “They have rigged up an excuse for a hospital on the outside, where the sick are taken. Admit none though who can walk or help themselves in any way. Some of our men are detailed to help as nurses, but in a majority of cases those who go out on parole of honor are cut-throats and robbers, who abuse a sick prisoner.” To top off these conditions, Ransom wrote that the Confederates didn’t even have medicine for ill soldiers (which, given the hostile environment, isn’t super surprising).

Although I’m actually saddened to know that my grandfather was in the hospital and may have been subjected to the cruel treatment that Ransom described, it does offer me more information–and even some closure–about what he experienced while there. Additionally, I know that Grandpa Jesse’s time in the hospital lasted just over a week, since the record indicates he was admitted April 25, 1864, and passed away May 4, 1864.

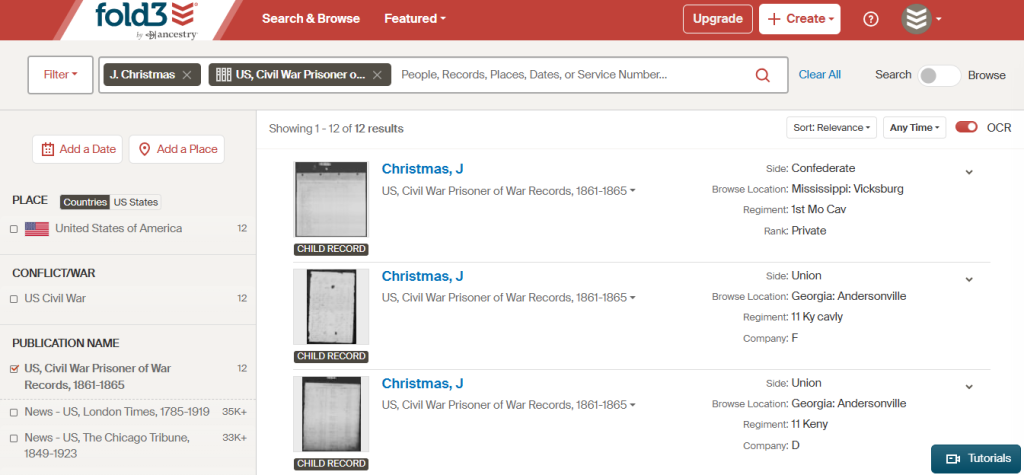

*John Ransom, in his “Andersonville Diary,” noted that about one hundred soldiers were in every squad. He wrote: “We are divided off into hundreds with a sergeant to each squad who draws the food and divides it up among his men, and woe unto him if a man is wronged out of his share—his life is not worth the snap of the finger if caught cheating.”

Research Tips

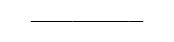

When it comes to searching historical records, one of my best suggestions is to start with a broader search before narrowing down your hunt. However, these latest Fold3 records are a bit different, because even the Fold3 team suggests that researchers search using only their ancestor’s first initial and last name. As one can see–based on the image above–I didn’t type “Jesse Christmas” into the search bar. To follow Fold3’s guidance, I instead searched “J Christmas,” which yielded the results that I needed.

Of course, since “J Christmas” is a broader search (it could stand for John Christmas, Joe Christmas, or any other “J” combination!), many of the results weren’t exactly specific to my ancestor. In fact, the very first “J Christmas” listed was a Confederate soldier, whereas my ancestor was a Union infantryman who fought with the 11th Kentucky. To help eliminate the records that don’t pertain to your relative, you can check out the soldier’s regiment on the far right hand side of the screen.

For some soldiers, you might even find it helpful to search by last name only. As an artifact collector, I have one relic that belonged to Charley Henry Howe (36th Massachusetts Infantry) who was captured and confined at Andersonville, where he ultimately died of scurvy. Because Charley often went by his middle name, too, I had difficulty just finding a “C Howe” that lined up with Charley’s regiment. As such, I searched “Howe” and–after sorting the entries by A to Z–navigated to the Cs. After doing that, I was finally able to uncover Charley’s records under “Howe, C H.”

In Conclusion

No matter whether you’re a descendant–like me–of a prisoner of war or you’re just passionate about honoring these POWs, Fold3’s latest record offerings provide important information about these soldiers’ experiences. From understanding soldiers’ causes of death and when they were admitted at the hospital to uncovering their squad number, prisoner of war records offer some never-before-available details that are essential to serious researchers. In light of my upcoming “pilgrimage” to visit my grandfather’s grave at Andersonville, I’m happy to have a little more of a glimpse into his unique war-time experiences.

Keep the History Alive!